Prevent This: Fake Domain Attacks

Attackers are registering website addresses that look exactly like file names you'd download, tricking people into visiting malicious sites when they think they're opening a document.

Happy (belated) Thanksgiving!

To all of you subscribers in the US, Happy (belated) Thanksgiving! I hope everyone got to spend some time with family. At Intruvent, we’ve been busy cooking up some magic ourselves. I hope to be able to share some cool news with you in next week’s newsletters!

Now on to your regularly scheduled edition of Prevent This!

What Happened?

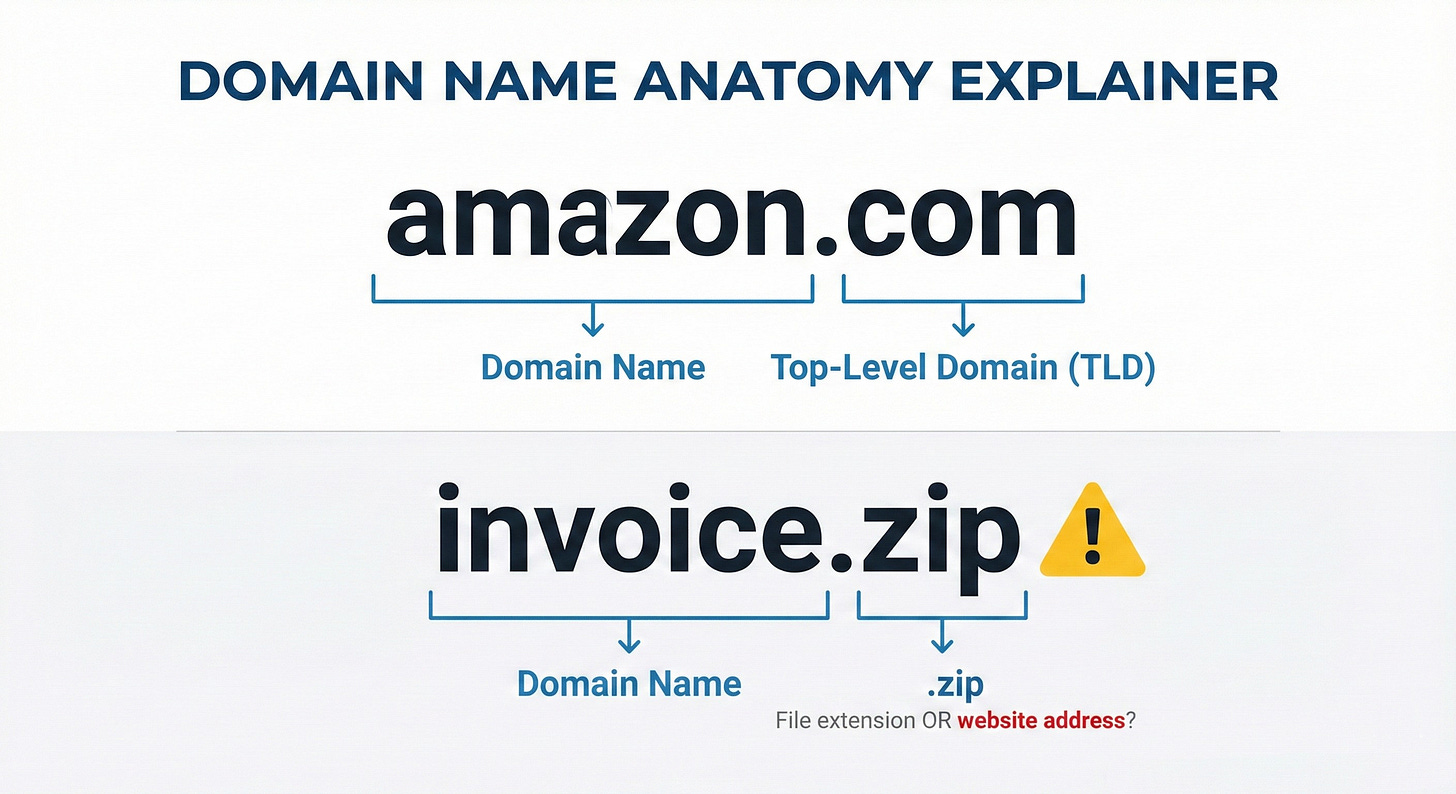

Website addresses end with things like .com, .org, or .gov. These endings are called “top-level domains” or TLDs. The .com in amazon.com stands for “company” and tells your computer to look up a website address. There are other popular TLDs like “.net” (network), “.org” (organization) and “.ai” (artificial intelligence).

Here’s where it gets weird: In May 2023, Google opened up new website endings for anyone to purchase, including .zip and .mov. If you’re an experienced computer user, you recognize those as file types. A .zip file is a compressed folder you download. A .mov file is a video.

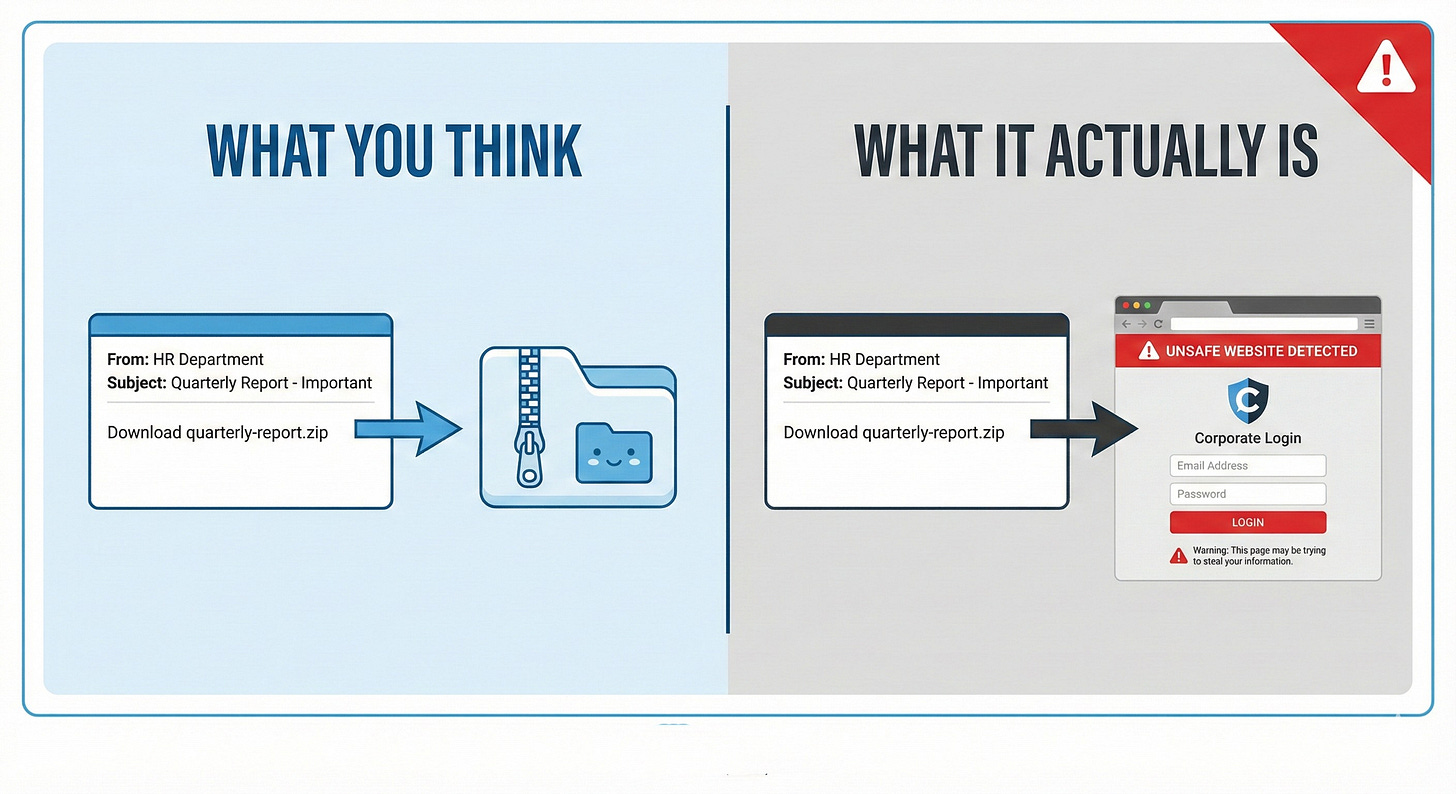

Now someone can register “quarterly-report.zip” as an actual website address. When your colleague emails “download quarterly-report.zip and review before the meeting,” your brain sees that .zip and thinks “file to download.” But it’s actually a website that could steal your credentials or install malware.

Why Should You Care?

This attack exploits a lifetime of computer habits. For decades, .zip meant a file you download and open. Now it can also be a website you visit. Our muscle memory works against us.

The problem compounds because many applications automatically turn anything ending in .zip into a clickable link. Someone types “open the document.zip file I sent” in a Teams chat or email, and “document.zip” becomes a hyperlink pointing to a website the attacker controls. You click expecting your file and land on a phishing page designed to harvest your password.

Researchers have already spotted domains like microsoft-office.zip and officeupdate.zip in active phishing campaigns. One year after Google launched these domains, research from EfficientIP found that 60% of identified malicious .zip domains remained active and operational.

How Does This Work?

Security researcher mr.d0x developed a technique called “file archiver in the browser” that makes this especially convincing. The attacker builds a webpage that looks exactly like WinRAR or Windows File Explorer showing the contents of a ZIP archive. You think you’re looking at files inside a compressed folder, but you’re actually on a website. When you “click to extract” a file, you either download malware or get sent to a credential-stealing page.

There’s also a Unicode trick that makes fake URLs appear legitimate. Attackers can craft links that look like they go to GitHub or other trusted sites but actually redirect to their malicious .zip domain. The forward slashes in the URL are actually special Unicode characters, so your browser interprets the destination differently than your eyes do.

What Can You Do About It?

For Everyone: Look carefully before clicking any link ending in .zip or .mov. Ask yourself: is this a file someone attached, or is this a website address? Hover over links without clicking to see the actual destination. If someone tells you to download a .zip file, look for an actual attachment icon rather than clicking a link in the message body.

For IT Teams: Consider blocking .zip and .mov domains at your firewall, DNS resolver, or web proxy level. If your organization has no legitimate business reason to access these TLDs, blocking them removes the risk entirely. You can whitelist specific domains as needed. Train users specifically about this threat, emphasizing that .zip and .mov can now be website addresses.

For Everyone Again: The same fundamentals apply here as with any phishing attempt. Be suspicious of urgency. Verify through a separate channel if something seems off. Don’t enter credentials after clicking a link in an email or message. Go directly to the site by typing the address yourself.

The Bottom Line

The internet’s naming system now includes website addresses that look identical to files you’d download. Until your brain adjusts to this new reality, slow down and verify before clicking anything ending in .zip.